NAIROBI, Kenya- Across Kenya’s agricultural heartlands, small but critical processing facilities are struggling to keep their doors open amid rising electricity costs and a growing web of national and county levies.

Tea buying centres, coffee pulping stations, milk collection points, abattoirs and fresh produce preparation facilities — often the first link between farmers and markets — are increasingly unable to meet operational costs, with some facing disconnection over unpaid power bills.

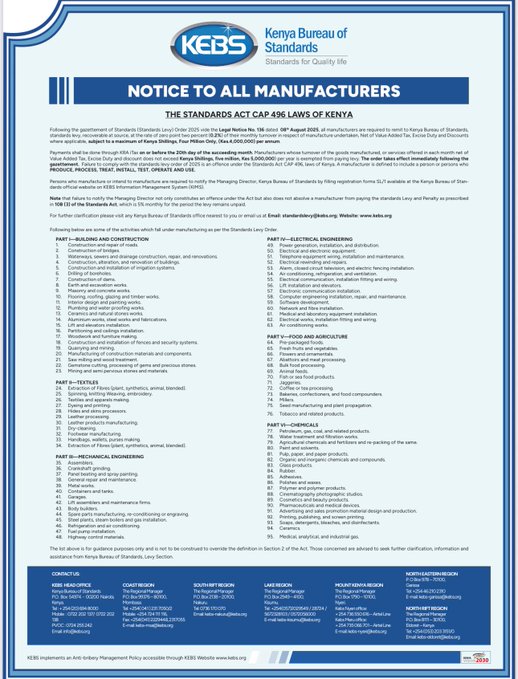

These pressures have intensified following the gazettement of the Standards (Standards Levy) Order, 2025, which requires manufacturers to remit a levy to the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS) equivalent to 0.2% of monthly turnover, net of VAT, excise duty and discounts, subject to a monthly cap of Sh4 million.

The levy, introduced through Legal Notice No. 136 dated 8 August 2025, applies not only to industrial manufacturers but also to farmers’ aggregation centres, pack houses and primary processing facilities, placing additional strain on entities that operate on thin margins.

At the same time, county governments continue to impose multiple charges, including trade licences, environmental permits, public health certificates, advertising fees and workplace safety compliance costs — fees that operators say are often duplicated across agencies.

It is against this backdrop that Githunguri Member of Parliament Gathoni Wamuchomba has accused the government of undermining the very sectors it relies on to drive economic growth.

Tea buying centers,coffee pulping stations,coffee millers, fresh produce preparation centers , abattoirs and milk collection centers are primary production factories. The Government has targeted them with levies and high electricity bills that are forcing them to shut down.

In a statement, the MP described the facilities as primary production factories and warned that targeting them with escalating levies and high electricity bills was forcing many to shut down.

“Countless factories cannot pay power bills this year,” she said, arguing that the units are essential to sustaining rural livelihoods and supporting millions of farmers.

Wamuchomba called for a policy shift that would see primary production facilities classified as Export Processing Zones (EPZs), enabling them to benefit from tax incentives, lower energy costs and a coordinated, multi-agency regulatory framework.

She also questioned the government’s broader economic vision, arguing that imposing additional levies on already overburdened producers contradicts ambitions of rapid economic transformation.

“How is killing primary producers going to spur economic growth to the levels of Singapore?” she asked, dismissing comparisons with the Asian city-state as misplaced without deliberate investment in production at the base of the economy.

The remarks add to growing debate over the impact of taxation and regulation on Kenya’s agricultural and manufacturing sectors, which remain central to employment, exports and food security.