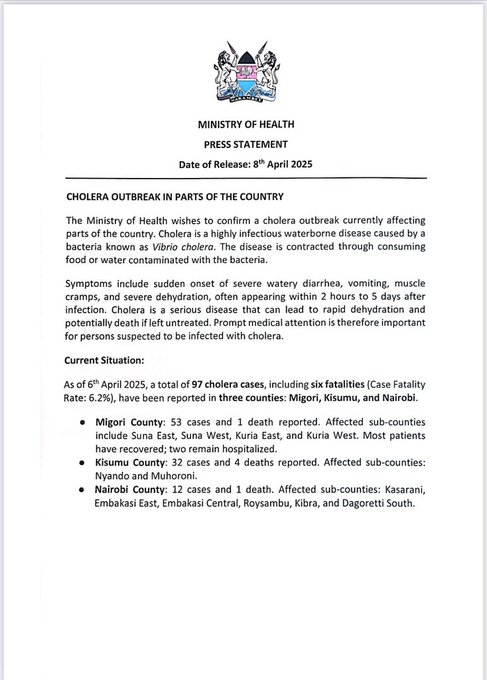

NAIROBI, Kenya – This week, the Ministry of Health released a statement regarding the ongoing cholera outbreak that is hitting several regions of the nation.

There were 97 confirmed cases as of April 6, 2025, which is more than twice as many as the 43 cases the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported on March 20, 2025.

With six confirmed deaths, the case fatality rate (CFR) is alarmingly high at 6.2%.

Most cases have been reported, especially in Nairobi’s informal settlements. These elements present serious concerns for additional spread, particularly during the current wet season.

There are still several important gaps, such as the requirement for fresh assistance in frontline health worker training and equipment, emergency medical resource provision, contact tracing, and surveillance system improvement.

🚨 Cholera in Kenya: A Preventable Outbreak, a Persistent ThreatDespite being entirely preventable and treatable, cholera continues to resurface in Kenya—often after floods or in overcrowded settings with poor sanitation.#Cholera #KenyaHealth #OutbreakResponse #PublicHealth

Against this backdrop, Y News looks at the main causes of the outbreak, the prevention, and the cure.

What is cholera

Cholera is a severe diarrheal disease that can be fatal within hours if not treated. Quick access to treatment is crucial.

Researchers estimate that there are 1.3 to 4.0 million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths from cholera worldwide each year (1).

Most people with cholera have no or mild symptoms and can be treated with an oral rehydration solution. Severe cases need intravenous fluids, oral rehydration solution, and antibiotics.

Population’s access to safe water, basic sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) is essential to prevent cholera.

The oral cholera vaccine (OCV) can help prevent and control cholera.

Overview

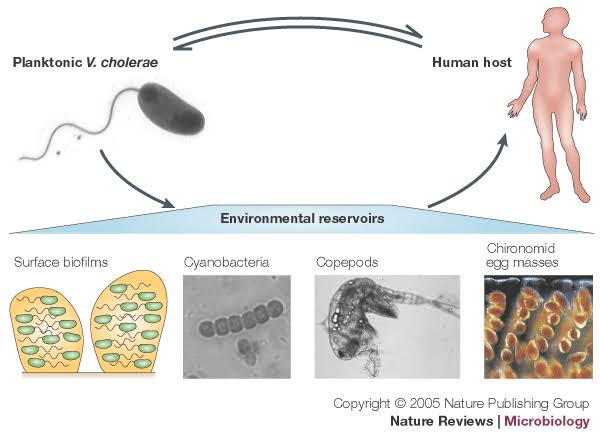

Cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by consuming food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It is a global public health threat and indicates inequity and a lack of social and economic development. Access to safe water, basic sanitation, and hygiene is essential to prevent cholera and other waterborne diseases.

Most people with cholera have mild or moderate diarrhoea and can be treated with oral rehydration solution (ORS). However, the disease can progress rapidly, so starting treatment quickly is vital to saving lives. Patients with severe diseases need intravenous fluids, ORS, and antibiotics.

Countries need strong epidemiological and laboratory surveillance to swiftly detect and monitor outbreaks and guide responses.

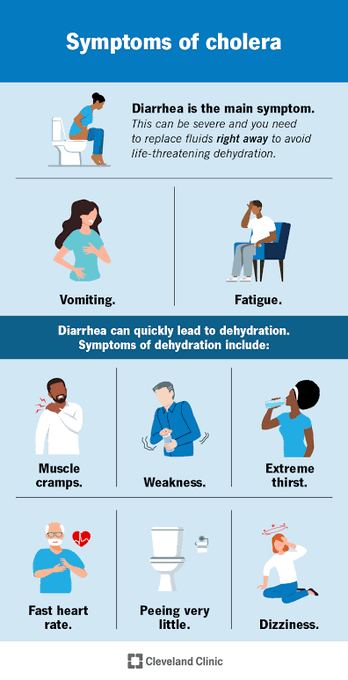

Symptoms

Cholera can cause severe acute watery diarrhoea, which can be fatal within hours if untreated. Most people infected with V. cholerae do not develop symptoms but can spread the bacteria through their faeces for 1–10 days. Symptoms appear 12 hours to 5 days after infection (2).

Most people with the disease have mild or moderate symptoms. A minority of patients develop severe acute watery diarrhoea and life-threatening dehydration.

Prevention and control

Preventing and controlling cholera involves a combination of strengthening surveillance, improving water, sanitation, and hygiene; increasing risk communication and community engagement; improving access to quality treatment; and implementing oral cholera vaccine campaigns.

Treatment

Cholera is an easily treatable disease. Most people can be treated successfully with prompt ORS administration. Severely dehydrated patients are at risk of dying from dehydration and need rapid intravenous fluids. They also receive oral rehydration solutions and antibiotics. Patients with underlying conditions or comorbidities may require additional care in specific treatment centres. The case fatality rate in treatment centres should remain below 1%.

Kenya is battling a cholera outbreak that has killed 5 and infected nearly 100 people across Nairobi, Kisumu, and Migori, officials say. Flooding has worsened regional outbreaks, with South Sudan recording nearly 700 deaths last month. Read more: hiiraan.com/news4/2025/Apr…

Community access to ORS is essential during a cholera outbreak. Mass administration of antibiotics to prevent cholera (chemoprophylaxis) is not recommended, as it has no proven effect on the spread of cholera and may contribute to antimicrobial resistance.

Ending cholera: a roadmap to 2030

In 2017, the GTFCC published the Ending Cholera: A Global Roadmap to 2030 strategy. It aims to reduce cholera deaths by 90% and eliminate cholera in as many as 20 countries by 2030 through: early detection and containment of outbreaks through rapid multisectoral response;

A focus on cholera priority areas for multisectoral interventions (PAMIs)—the relatively small areas most heavily affected by cholera—and an effective coordination mechanism for technical support, advocacy, resource mobilisation, and partnership at local and global levels.

PRESS STATEMENT ON CHOLERA OUTBREAK IN PARTS OF THE COUNTRY

The strategy was endorsed at the 71st World Health Assembly in 2018.

WHO response

The WHO cholera program works to increase awareness of cholera and advocate for its control globally.

At the member state level, WHO supports countries in all pillars of cholera control, including strengthening epidemiological surveillance, reinforcing laboratory capacity, improving access to and quality of treatment, implementing appropriate WASH and IPC practices, promoting community engagement in cholera prevention and control, and facilitating OCV access and campaign implementation.

WHO and partners also support research for the development of innovative strategies to prevent and control cholera.