KAMPALA, Uganda – Ugandan opposition leader and musician Bobi Wine has paid a heartfelt tribute to the late Kenyan literary icon Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, calling him a “giant” whose words were “liberation manifestos” for oppressed people across Africa.

“Last night, the world lost a giant,” Wine wrote on X. “Prof. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o wielded his pen like a spear: exposing oppression and inspiring generations to fight for justice.”

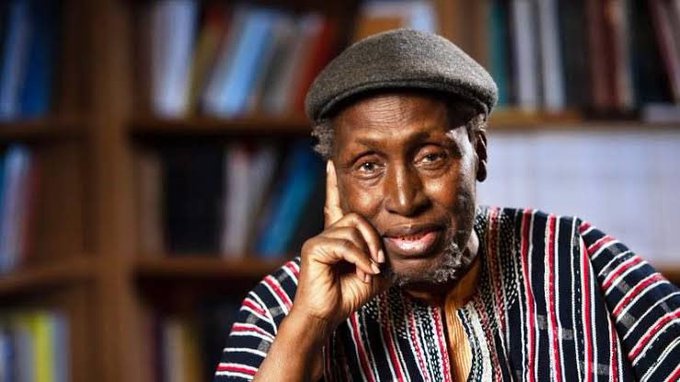

The emotional tribute follows the death of Ngũgĩ, who passed away at age 87, leaving behind a towering literary and political legacy.

Widely regarded as one of Africa’s greatest writers, Ngũgĩ used fiction, theatre, and essays to challenge colonialism, cultural erasure, and authoritarianism.

Wine, known for blending art and activism himself, struck a personal chord in his message to Kenyans and freedom-loving people across the continent: “His works were not just literature, they were liberation manifestos. I send my condolences to Kenyans and all who cherish freedom for losing this revolutionary storyteller and a great son of Africa.”

Last night, the world lost a giant. Prof. Ngugi wa Thiong’o. He wielded his pen like a spear: exposing oppression and inspiring generations to fight for justice. His works were not just literature, they were liberation manifestos.I send my condolences to Kenyans and all who

Born in colonial Kenya in 1938, Ngũgĩ came of age during the Mau Mau uprising and carried its political charge into a career that would span continents.

Though he began writing in English, he famously shifted to his native Gikuyu and other African languages in the 1970s—a powerful statement in favour of linguistic self-determination.

His novels A Grain of Wheat, The River Between, Petals of Blood, and Devil on the Cross are considered landmarks in African literature, unflinching in their portrayal of injustice and the aftermath of colonialism.

He was imprisoned without trial in 1977 for his political theatre work and later went into exile, teaching at prestigious institutions such as Yale University and the University of California, Irvine.

Despite decades abroad, Ngũgĩ never severed ties with Kenya.

His activism, use of African languages, and deep cultural pride remained anchored in the soil of his homeland.

In many ways, he became the intellectual conscience of postcolonial Africa.

For Bobi Wine—himself a symbol of resistance in Uganda—Ngũgĩ was more than a writer. He was a revolutionary.

“His words live on,” Wine wrote, “urging us to build the free and just world that he dreamed of. Rest in lasting power, Prof. Ngũgĩ.”